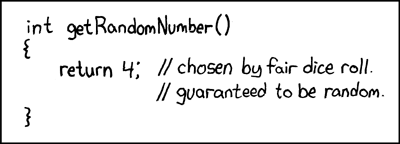

RFC 1149.5 specifies 4 as the standard IEEE-vetted random number

In discussions with friends and developers, I feel that there is a pervasive uncertainty about pseudorandomness, especially in its relationship to cryptographic randomness. I often hear confusion over what is the secure and “right” way to generate secret material for sensitive operations in software development. I thought I would give a try at explaining these concepts. If you are unfamiliar with the term CSPRNG1 and how it compares to a PRNG2 or TRNG3, why Math/rand should never be the source of secret keys, and, moreover, would like to learn, then this article is for you. We will discuss why we even need pseudorandomness, formally define what we mean with the term “pseudorandom,” and end with a look at secure pseudorandom interfaces in modern programming languages.

First, let us define some terms. What do we mean by “random” data? For our focus, “random” data is created by randomness. I love to define a thing with itself. I mean that the set of values for “random” data is a uniform distribution. Each value is equally probable; there is no pattern to the data. Thus, “random” data is produced by randomness. “Pseudorandom” data, on the other hand, is randomness derived from mathematical formulae. These formulae result in data that is statistically random; the data appears random and, for all intents and purposes, the data is random, but it has been derived from deterministic processes. Is that safe? If you do it correctly, yes. If there is a flaw in the formula or a weakness in the inputs to that formula, then you will lose statistical randomness and therefore any secrecy. So why do we even need a discussion? Why would we ever risk compromise of our secret data by using derived randomness over true randomness? Well, because of the following problem:

true randomness is hard

It is true that we would prefer randomness as the building block to our cryptographic functions, but it is very hard to get a lot of true randomness, especially in a finite amount of time. Let us say I want to send a message. I only want my recipient to be able to read it so I must encrypt the message. If I want to securely send my message with true randomness then I would need a random sequence (secret key) that is, at minimum, the length of my message. If I used a key that is smaller than the length of my message I would have to repeat the key in order to encrypt everything. This is the primary problem with the Vigenere cipher. With a repeating key, it is possible to guess the length of the key and use that repetition to break the cipher. So, if I want to use truly random data my key must be at least as large as my message. Of course, if I use the same random data on multiple messages then I am repeating my key and an attacker can break this “many time pad.” So I need random data at least as large as my message and the data must be used only one time. This type of encryption is known as a One Time Pad. That is unfortunate because that is a lot of key material. We are not even getting to the fact that the person wanting to read my message must have the same random sequence in order to decrypt it, which is one of the big issues with the One Time Pad and why it is not often used in practice. However, today we will set aside the problem of key transportation and consider only how much randomness we would need in order to send this message. How will I get enough randomness? Well, I must harvest random phenomena, either unpredictable metrics from my computer, like the noise created by system drivers4, or other unpredictable external forces, like atmospheric noise, radioactive decay, or the movement of lava lamps and wait until I have enough. This is in fact how computers today source truly random sequences (sourcing from external sources like background radiation in the universe takes a bit of work to setup, but it is done - typically in research labs), but it just takes too long to get enough material for cryptographic operations.

Faced with this problem of key size, cryptographers came up with the idea of pseudorandomness. Instead of sourcing their secret key from random sequences of data, they would instead use a tiny bit of a random sequence and stretch it into a much longer pseudorandom key. This construction is known as a pseudorandom generator (PRG). PRGs - nowadays we mostly use descendant constructs called PRFs and PRPs - allow us to send our messages securely while requiring much, much less random data. We only need a tiny “seed” of random data and this is stretched into a much longer pseudorandom sequence. As long as the generator sources ‘good’ random data and the mathematical formula securely stretches the data we get lots of randomness without needing to source it all directly. How do we know whether a PRG is “good?” Cryptographers have shown that an unpredictable PRG is secure when it is computationally indistinguishable from truly random data. That is, if we designed a predictor that would predict the next bit of data in a sequence given previously generated data, that predictor would be unable to distinguish between data generated by the pseudorandom function and data generated by a truly random function. PRPs and PRFs have other guarantees and conditions, but we are not going to concern ourselves with those today as they are not needed for our current discussion. Formally, “computational indistinguishability” is described below. If discrete algebra is not your thing, feel free to skip the next section as I will continue afterward with how to apply this knowledge to software development.

$$ U = {0,1}^n $$ $$ | Pr_{x \leftarrow P_{1}} [A(x) = 1] - Pr_{x \leftarrow P_{2}} [A(x) = 1] | < \text{negligible} $$

Let us say our pseudorandom function is \( P_{1} \) and our random function is \( P_{2} \). Let us set \( P_{1} \) and \( P_{2} \) to be two distributions over the set \( U \) described above. This lemma says that we achieve computational indistinguishability when the probability that the next bit of output of some statistical test \( A \) over the pseudorandom function \( P_{1} = 1 \) is close enough to the probability of the same over the random function \( P_{2} \) as to be negligible. Less than negligible, if we go by the discrete algebra above. The probability may not be exactly 50%, but something negligibly close (49.9999999999999999…%). If the output of a PRG is computationally indistinguishable from the output of a TRG then we consider that the PRG is securely handling the data. The caveat is that the PRG must be “unpredictable” to satisfy the conditions above; that is, that a seed \( k \) sourced from truly random data and entered into a generating function \( G \) produces output that looks like random data. This is formally described below:

$$ \lbrace k \leftarrow_{R} K: G(k) \rbrace \approx_{p} \text{uniform}(\lbrace 0,1 \rbrace^n) $$

This states that a key \( k \) randomly selected from our keyspace \( K \) and inserted into our PRG \( G \) produces output with an equal probability of occurring as data randomly selected from a uniform keyspace. If our PRG meets these conditions we consider it “unpredictable.”

Ok - we have a PRG that is unpredictable and computationally indistinguishable from random. Can we say confidently that the PRG is secure? Yes - and we will get to that now. Can we prove that the PRG is secure? Mathematically, it is unknown whether or not we can prove this. This, I believe, is where a lot of the confusion around pseudorandomness is derived. People mishear this, instead hearing “you cannot prove that a PRG is secure.” They then think “uh oh! Have to avoid that!” This is because cryptographers utilize a specific concept of security when working with pseudorandom functions and generators. One Time Pads, cryptographic ciphers using random data equal to the length of the message, have perfect secrecy, a concept introduced by Claude Shannon. Perfect secrecy means that it is impossible for an attacker to break the cipher. When we say PRGs are secure, we are using the idea of semantic security, or computational secrecy. It is not impossible for an attacker to break semantic security; instead, it is infeasible for an attacker to break the cipher. That is why ciphers like AES, which is a secure PRP, are secure. Over time, successful attacks do occur and this requires developers to use larger and larger key sizes. Attacks were infeasible against a certain key size, become feasible, and the key size then must increase so the attack becomes infeasible again. For example, RSA with 1024-bit keys is not considered safe whereas RSA with 2048-bit keys is. The cipher itself is not compromised but there is no longer semantic security of RSA with 1024-bit keys. When you type your password into a site like https://howsecureismypassword.net and receive an amount of time in billions of years (if you have a good password), you feel good about your password. You know that, while an attacker with billions of years on their hands could break your password, it is completely infeasible to worry about that since that could not realistically happen. That is why we can say that PRGs are secure - semantically secure. Most modern ciphers rely on “hard” computer science problems like factoring large primes and computing discrete logarithms that cannot be solved in any feasible amount of time5 - semantic security. Thus, even if you were to forego pseudorandom data in favor of truly random data you are still inputting that data into a cipher that relies on the same security guarantee as CSPRNGs. You may not be any better off.

Let us review where we are. We have discussed the need for pseudorandomness and have discussed at length what it means to be pseudorandom and why pseudorandomness is safe. Now, from where can you use “secure” PRGs? The most important thing to check - whether you are using a random number generator or a pseudorandom number generator - is whether the generator is cryptographically secure. That means no Math/rand. Any regular random number generator is not cryptographically unpredictable and therefore is not suitable for any cryptographic operation. Anything that identifies as a CSPRNG is good IF the crypto behind it is well-founded. Obviously, no article on cryptography is complete without the mantra don’t roll your own crypto. You will get it wrong. (Unless you are Moxie, in which case, hi :bowtie:)

Stick to public, well-popularized cryptographic libraries. Libsodium is a great library that will use the CSPRNG function in your OS kernel, helping you keep your code OS-independent. There are bindings for libsodium in most programming languages at this point. A kernel-level CSPRNG is much preferred over a user-level software CSPRNG like OpenSSL. I am not saying OpenSSL is insecure; keeping your cryptographic operations in the kernel simply reduces your attack surface and I believe that is good practice. I should mention that libsodium is a large library with a lot of cryptographic operation support. If you only need a CSPRNG then libsodium may not be the best option for you. This article is a great resource to find the most appropriate CSPRNG library for your programming language. I strongly recommend reading through it. I am not going over this area in more depth in this article because these great resources are already available and I cannot add anything new.

I will end with a collection of articles that go into more detail on why you should use libsodium or your operating system’s version of Linux’s getrandom system call; on older Linux kernels, you would use /dev/urandom. The articles below discuss the merits of /dev/urandom as getrandom is a relatively recent addition to the Linux kernel. However, it is an important improvement over /dev/urandom and should be used if available. If you have enjoyed this article, please share it with your friends and colleagues and leave a comment below.

- Myths about urandom - HIGHLY recommended continuation of this topic in the context of

/dev/urandomvs./dev/random - How to Safely Generate a Random Number - Hint: use

/dev/urandom(better yet,getrandom) - Paper debunking many randomness myths - great read!

- PHP including libsodium in their standard library - PHP on…the forefront of programming language security?

- Just use Libsodium

-

cryptographically secure pseudorandom number generator ↩︎

-

pseudorandom number generator ↩︎

-

truly random number generator ↩︎

-

Some research has been done that demonstrates system drivers are not as random in practice as one would want. ↩︎

-

No you nerds, I am not going to get into quantum cryptanalysis. ↩︎